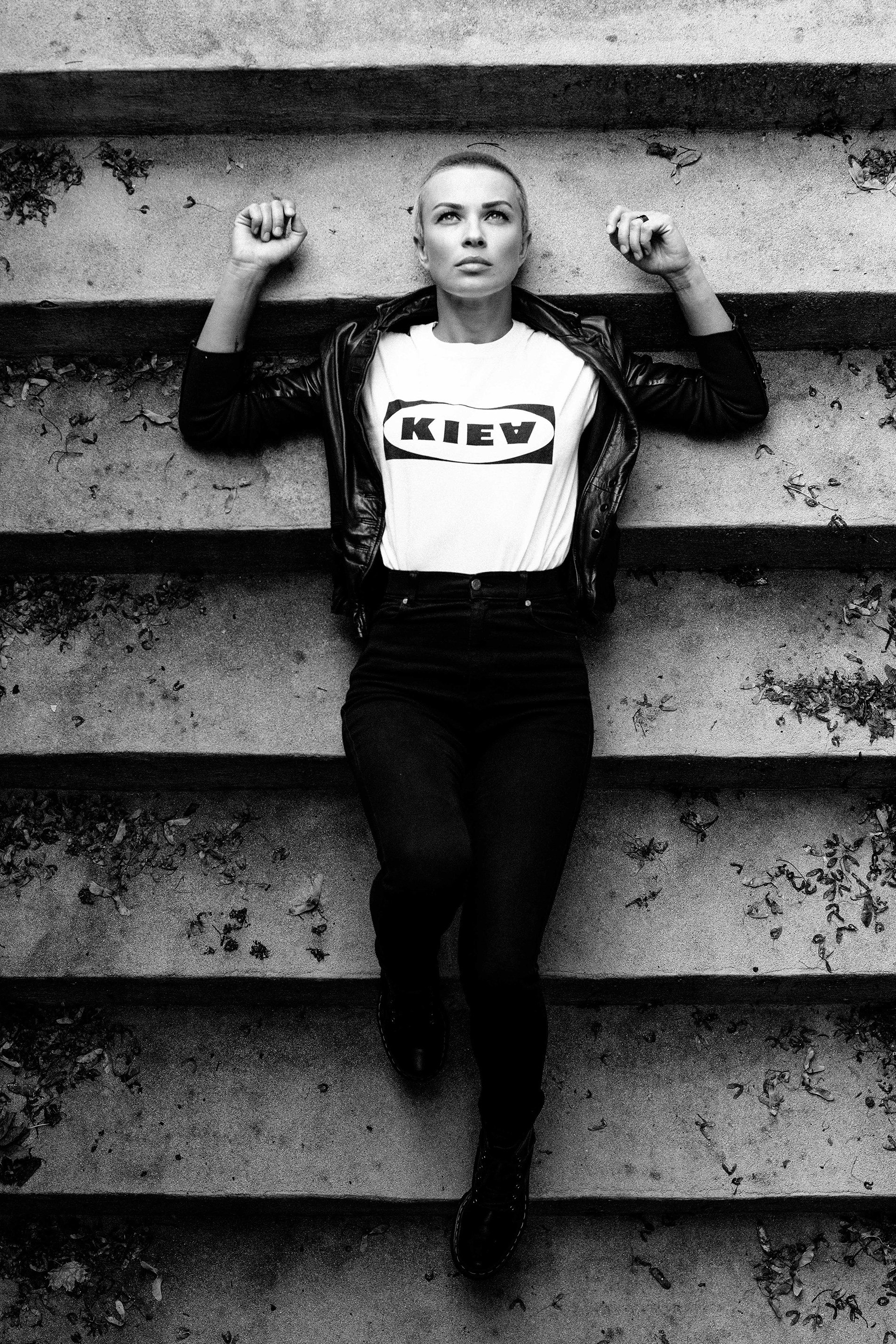

Nastia: Battling Demons

Anastasia Topolskaia opens up to Carlos Hawthorn about the pressures of life as a touring DJ.

Dawn beckoned as I walked into Watergate. The Berlin club’s main dance floor, throbbing to the pulse of LEDs, was roughly half full. Anastasia Topolskaia, the Ukrainian DJ better known as Nastia, was smiling and rocking gently behind the decks. The music stood out for its quirkiness: swinging tribal tracks flowed into hectic breakbeats peppered with squeals and other freaky sounds. She mixed with impressive agility across three CDJs—as soon as a track was out of the mix, she was working the next one in. At one point, a young girl, wide-eyed and friendly, extended a hand into the booth. Topolskaia squeezed it tenderly and smiled.

I honestly wasn’t sure what to expect from Topolskaia, a DJ who occupies a curious position between, for lack of better terms, the underground and the mainstream. It was my first time seeing her play. Up until then, my opinion was based on two excellent mixes—Boiler Room and the BBC Radio 1 Essential Mix—both of which show a DJ with broad tastes and a love of nerdy sounds. (The Essential Mix, from July 2017, runs the gamut from Luke Slater and Aleksi Perälä to golden-era Skream.)

Topolskaia rarely gets a chance to play this kind of music out, except at a few key places, like Closer, the Kyiv venue that’s currently considered one of the world’s best clubs. She plays there two or three times a year, including at the annual Strichka Festival, which she runs in partnership with the Closer team.

“I trust our people,” she told me over a long lunch in Berlin. Sharp and with a dry sense of humour, she spoke with a constant twinkle in her eye. “They’re so educated. So cool. So open-minded. They don’t want you to play normal; they want you to play freaky and crazy and weird. I appreciate it. That’s where I’m real. Maximum me.”

Mostly, though, Topolskaia plays more functional techno and house to large crowds. Every year, the shows get bigger. A few weeks before the Watergate gig, she spent eight days on the road with Carl Cox in Australia and New Zealand, playing to thousands almost every night. More recently, she visited Japan to complete a run of Asia gigs for Ultra Music, arguably dance music’s biggest promoter.

Topolskaia is far from the only artist occupying these two worlds, but she feels particularly uncomfortable doing so. During our three-hour conversation, she spoke candidly and at length about the stresses and pressures of playing large events. She feels most free at smaller shows, where she gets to play deeper music to intimate audiences.

“People always expect something from you,” she said, piercing ravioli with her fork. “My favourite thing to do is to play dubstep or experimental tracks and watch people’s reactions. They just stand and stare. Some of them I’m sure are thinking, ‘What is this bullshit?’ Some are probably like, ‘Wow I never heard something like this.’ I’m curious to see the faces, they change. Because if you play functional music, they talk to each other, they’re having a normal party, but then you drop something weird and you get attention. It might be bad attention. But still you need to be strong, stronger than the audience to overcome the pressure from the dance floor and say, ‘No guys, you gonna listen to this right now.’ Otherwise I don’t understand what I’m doing here.”

Topolskaia feels especially conflicted about festivals, which, for better or worse, are a sizeable chunk of her current bookings. “I don’t get this festival thing, honestly,” she said. “People are too far away. How can you connect with them? How can you see what they like? You don’t care about them, they don’t care about you.”

She continued: “But I do these shows because it’s training. It’s always a challenge. Big festival, big crowd. You really need to be good at playing big music, big sound. I actually came from house music, more micro house, minimal, and then I had to learn how to play bigger and bigger. I’m still learning. It’s not easy for me. I still love minimalistic sounds. And I don’t enjoy playing big tracks, one by one. In the end it’s just noise. Just ‘bam, bam, bam.’ What is that? People come for this?”

Topolskaia’s brutal honesty threw me a little, but it didn’t come as a total surprise. Anyone with even a casual interest in her social media channels will know she’s very active and often outspoken, writing long posts on Instagram about life on the road. Most shows get a detailed post-match report. Plenty, like this recent one from Ibiza, are glowing, but some are less so. A couple weeks after we spoke, she played Riverside Festival in Glasgow. “After @patricktopping I have killed the stage,” she wrote. “I think it might be wrong set and wrong music, or I am just absolutely not popular in Glasgow.”

You can trace this self-reflection all the way back to 2009, the year that everything changed for Topolskaia. At that point, she had been a professional DJ for four years, playing trance, tribal and prog house at clubs around Ukraine as DJ Beauty, a name given to her by an ex-boyfriend. (“I was so silly, 17 years old.”) Before that, she was a go-go dancer in Donetsk, the city where she went to university and where, as a young teenager, she would travel regularly to visit her two older sisters, who would take her raving and to the local market to buy pirate CDs of movie soundtracks. (Her favourites were The Matrix and Frédéric Garson’s The Dancer.)

When she stopped dancing and first took an interest in DJing, around 2004, she would source her tracks from a tech wizz in Donetsk, who had set up a business in his apartment selling pirated CDs of ripped or illegally downloaded dance music.

“You would spend the whole day there and listen to as much as you can, then he would burn the CDs in front of you,” she said. “It’s so crazy—I still remember I went once and the guy played “Bubblebath” by Baby Ford & Mark Broom. I was like, ‘What is this?’ I remember the moment. I was sitting next to my boyfriend. He told me the name and I was like, ‘This one, this sound, this is mine.'”

Despite this epiphany, it would be another five years before Topolskaia could fully indulge her tastes for such stripped-back sounds. In the summer of 2009, after three years living in Kyiv, she split from her first husband, the DJ and promoter Anatoly Topolsky, who’s considered the father of drum & bass in Ukraine. She moved with their one-year-old daughter to a flat in the city centre and, broke and gig-less, began calling all the promoters she knew, offering to play for half her usual fee.

“I had nothing,” she said. “I remember breaking piggy banks so we could buy bread and noodles. Some of the promoters helped me, so I could at least pay for the car and the apartment. But it was minimum, minimum. That summer was the lowest point of my life, I think.”

The first in a series of lucky breaks happened around this time, while Topolskaia was hosting a show on the radio station Kiss FM Ukraine. When she asked the station manager if he had any paid work going, he said he didn’t, but if she wanted she could manage the Kiss FM stage at Kazantip, the zany month-long festival that took place in Crimea between 1992 and 2013.

“I went full of energy because the last two and a half years I hadn’t used any,” she said. “It was an explosion. That season was so amazing.”

You can see how much Topolskaia enjoyed Kazantip that year from this video, which shows her, some time into a nine-hour DJ set at the closing party, dancing furiously to the churning techno track “Medusa” by Loco & Jam. (By that point, she was going under the name DJ Nastya Beauty.) The clip went viral, clocking up almost 700,000 plays on YouTube and possibly millions more on the Russian social media network VKontakte. Her bookings skyrocketed—suddenly she was playing every weekend between Russia and Ukraine. On March 5th, 2010, she played her first show outside of those two countries, at a party in Bonn, Germany.

“Everyone was coming up to me and asking me to play ‘Medusa,'” she said. “I was so disappointed I was almost crying. I was trying to run away from this image. Run away from the video. I hated it.” For The Guardian‘s Harangue The DJ feature in 2017, she chose “Medusa” for “The track I wish I’d never played.”

Part of the reason Topolskaia wanted to leave the video behind was her new relationship with Arma17, the world-renowned promoter and now-defunct club in Moscow. She had met the founders, Natasha Abelle and Alexei Shelobkov, that same summer at Kazantip. Impressed with what “she was trying to do for the culture,” they offered her a residency. Over the moon, she accepted, but soon the new position began to weigh heavy on her shoulders.

“Since that moment, everything changed,” she said. “I changed—not because I had to fit into their group, but because I felt like I needed to change. Everything I had done before was in the past. I wanted to start something else, I wanted to be serious. I changed my name. I changed my Facebook page. Every time I went to play at Arma, I would try and push myself to play something special for these guys. I wanted their respect.”

She paused and looked down before continuing. “But now I understand when I cut this thing, I lost something. Something really important, this kind of pure energy. I wanted to be like them, which meant I didn’t want to be myself. But that energy didn’t go anywhere. It stayed in me. I was just suppressing it. It took me many years to realise that.”

My conversation with Topolskaia, coupled with her bare-all social media persona, suggested that these feelings of insecurity still linger. Despite being a successful international DJ she suffers from imposter syndrome, which sometimes manifests in ways that irritate sections of the dance music community. In July, following a nightmarish journey home from Romania, she took to Instagram to vent, complaining that she didn’t have enough time to properly prepare for her next gig, a vinyl-only set in Ibiza. “What a challenge and so much stress again,” she wrote. “I hate summer. I hate when everything goes against me.”

The post received a torrent of abusive comments, mostly criticising her apparent lack of gratitude for being a professional DJ. “You must be the most unlucky human being for not having appreciation for anything at all,” someone wrote. I get why the post riled people—well-paid DJs complaining about their lifestyle never goes down well—but from briefly getting to know Topolskaia, it’s clear these posts are a way of dealing with deep and complex feelings. She, as we all do, relieves stress by sharing her intimate thoughts with the people who care about her—in this case her 239,000 Instagram followers.

“I can’t handle it,” she said. “I can’t keep it in. If I don’t say it, it eats me up. I need to open myself up and let go in this way. I can’t do another way. Sometimes my manager says to me, ‘What did you write on Facebook? It’s gonna affect your career. Oh my god! What did you do?’ But I’m always honest. I prefer to lose the opportunity but to stay myself. Because this is what we miss in the scene. Everyone says, ‘Oh bomb, oh amazing, the show was so good etc.’ You remember the Tiga post from a few months ago? It was massive because it was real. It was finally real. And this is what I’m doing—not for promotion or support—but because I can’t do any other way. It just flows out.”

Topolskaia also admits that part of the problem is she’s playing too many gigs. “This is my weakness. I wish I could do less, but still I’m keeping going and doing as much as I can. I don’t have time to think. I don’t have time to analyse. That’s why sometimes I feel like a loser.”

Topolskaia doesn’t want to maintain this intensity forever, which explains why she’s playing so much now and accepting so many of the big shows. In two years, she told me, she wants to cut her schedule in half. She has other aspirations: to learn to meditate, to take up yoga, to have another baby. At some point, she wants to go back to university and study psychology. It’s easy to criticise DJs for chasing big offers, but the music industry is a fickle environment. There’s no guaranteeing where you’ll be in five or ten years. If, like Topolskaia, you have dreams outside of dance music, then maybe it makes sense to make hay while the sun shines.

“I want to do so many different things,” she said. “My list becomes bigger and bigger, but I never have time.”

Just after 6:30 AM at Watergate, with less than 30 minutes of the night remaining, Topolskaia eased in the tunnelling groove of “Bubblebath” by Baby Ford & Mark Broom. The dance floor had shrunk to a few dozen stragglers, all of them determined to follow her to the bitter end. After a closing run that included Gerd’s “Spective Status” and two encores, Topolskaia cupped her hands to her mouth, wished the crowd “a good day” and put down her headphones. A few fans scurried up to the booth to chat and give praise. I overheard a guy with bushy hair and a winsome smile complimenting her on a set at Harry Klein in Munich.

“I was terrible that night,” she said.

He looked slightly taken aback, the initial look of excitement slowly leaving his face. “For me it was good enough.”

Topolskaia leaned a little closer. “I can do so much better.”

Article Source: Resident Advisor